Beyond The Hype: Should You Invest In Deeptech Today?

We look at deeptech as an asset class and in particular in Europe to understand whether it's overhyped, underhyped or fairly assessed: and how can investors underwrite the asset class.

Deeptech: true revolution or a dot-com bubble repeat?

Just over half way into 2024, and news feeds overflow with tech breakthroughs –like AI chips, new artificial intelligence models, nuclear fusion and quantum computing leaps forward.

Is the excitement justified?

And even if it were: how can investors used to traditional software and “shallow tech” investing gain exposure to the asset class without getting burnt?

The Fundamentals

Let's start with the fundamentals. For starters, unlike fleeting trends like the dot-com boom or cryptocurrency frenzy, deeptech is a lot closer to the early days of the Silicon Valley tech boom. That is: their products are grounded in solid, groundbreaking technological developments that are finding their way into commercialisation and, in doing so, opening up new market opportunities that were just not possible beforehand.

Take the invention of the semiconductor in the 1960s as a classic example. This pivotal discovery paved the way for modern computers and smartphones, revolutionising how we work and communicate and leading to significant technological and economic growth. Those “fundamental technology” companies, often the brainchild of hardware engineers and even PhDs, are still dominating the innovation landscape ─think of Alphabet, Nvidia, Genentech, or Intel. Today, focusing on fundamental technology companies, i.e. deeptech, may feel just like another investment trend: and a scary and complex one at that. Especially after two decades when startup investing was preached on the dogma of “asset light” software companies. But by drawing parallels to the early days of Silicon Valley and pointing to resilient infrastructure technology companies who survived the last market correction and now dominate the stock market, it’s fair to say that deeptech may actually be inherently anti-trend and anti-fad. It’s about companies whose fundamental technology development carries both early R&D risks and strong defensibility moats that make them both resilient and extremely valuable in the long run. Almost irreplaceable in fact, as the tech monopolistic growth of ASML, Nvidia and TSMC prove today.

And the investment market is noticing this: in 2023, the resilience of deep tech investments was strikingly apparent. European deeptech companies, for example, have successfully secured nearly $15 billion in venture capital funding year-to-date, maintaining robust investment levels on par with 2022. This is in sharp contrast to the significant 70% downturn seen in sectors like fintech. Notably, the UK, France, and Sweden are leading in deep tech funding across Europe, with each country garnering around $3.2 billion. This sustained investment highlights the strategic significance of deep tech—not just as a thriving sector but as the foundation for revolutionary technologies that promise to reshape industries and drive future economic growth.

Beware of the doppelgangers!

As we delve into the deeptech revolution, it's important to recognise the difference between genuine deeptech startups and those merely trying to catch onto the trend, particularly in the AI space. Not every website or startup with a .ai domain qualifies as deeptech; some are merely capitalising on the generativeAI trend, but are firmly solving end-user application level problems, rather than fundamental technological challenges at the core, tech infrastructure level.

To identify authentic deeptech companies today, we must focus on two key aspects: the global problems they aim to solve and their fundamental business models. This is crucial because investment returns derive from a business model that not only identifies but also capitalises on these opportunities through a fundamental technological shift —and the technological shifts deeptech startups aim to commercialise stem from the fundamental nature of the problems they aim to solve.

Almost every industry seeks to integrate technology to sustain and enhance customer value. That’s why startups and the venture capitalists backing them have been so successful at creating innovation and industrial disruptions in the last half of a century. But deeptech companies go a level deeper and take on challenges that just cannot be solved with existing tech that’s repurposed and deployed as a cloud app. Before we explore how to identify these companies, let's first understand WHY a hard-to-build tech is essential to solve certain classes of problems.

Why are industries in a dire need of adopting deeptech?

The 2000s technology revolution gave us software, applications, and digital services that made our lives easier and more exciting. Consider Microsoft Excel, Amazon, Instagram, food delivery apps, ride-sharing apps, and the list goes on.

But what next?

Today, technology is not just limited to our mobile and laptop screens. It’s going beyond that, entering our cars, homes, workplaces, and even our environment to solve complex problems we face on a daily basis.

As you can see in Table 1, when it comes to innovation maturity vs level of interest over how much money has already flowed into a given “space”, we can see how energy transition, mobility, connectivity, and applied AI have taken the lion share of funding so far. But that applied AI and somewhat connectivity are already peaking in terms of innovation, being by now past the need for foundational tech breakthroughs and into the optimisation and commercialisation phase.

By contrast quantum technologies, space, edge computing, industrial hardware and even GenAI (at a foundational level) are only now getting started in both innovation and overall funding, despite the strong rise in recent years. Despite attracting strong funding, even climate, energy transition, mobility, and decentralised web still require a much higher level of innovation if they are to bring to market fully commercially viable solutions.

Despite some “climate” VC funds trying to ride the “ESG” wave by doing mostly software investment they then label as “impact” through box-ticking, you just can’t generate or store energy with pure software apps. Nor can you solve advanced mobility problems or develop a quantum computer with a lean SaaS app.

From the hardware to the software level, scientists and engineers need to commercialise entirely new technologies if their company is to solve pressing issues in these industries, like producing cleaner energy away from fossil fuels, developing new underlying paradigms in the chip and computing industry, or bringing about autonomous vehicles.

As I learned myself by specialising in investing in deeptech, there is almost a rule of thumb, whereby you don’t want to have more than a handful of potential competitors for any given novel deeptech solution and you want to have strong signals that the market would likely swing behind such solution “if only” it could be proven out of the lab and with sufficient scale. Otherwise it’s probably not deeptech or too much of a pure science project respectively.

A good case is for quantum technologies: it’s obvious that if we had a working quantum computer producing real results, governments and corporations would jump on it. They are pre-buying and investing in this possibility when it’s not even yielding any commercially viable results yet. However, the list of quantum startups actively developing critical components to make this a reality is actually fairly short globally (Dealroom in 2023 had just over 200 tracked) because the technology to achieve commercial breakthroughs has not yet been figured out in the first place.

On needs vs funding and identifying opportunity-yielding asymmetries

Climate technology, electrification, and the health sector are in the bottom five on the list of private equity investments made in 2022. However, they are the most prominent problems across the world that need to be addressed.

For example, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the predicted new cancer cases in the year 2050 will be over 35 million, a 77% increase from the estimated 20 million cases in 2022. This is concerning because one-third of cancer patients in the United Kingdom (UK) receive their diagnosis in emergency conditions.

Some challenges are related to the technological advancements for a sustainable future, like electric vehicles (EVs) in the automotive industry. Although the carbon emissions are lower compared to traditional vehicles, the distance covered by EVs on one charge poses a challenge for adoption. Consumers face a dilemma: whether to choose large battery vehicles for the long run, which deteriorate the environment, or small battery vehicles which need frequent charging, costing them heavily.

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) identified prominent challenges and key market insights in their Investors Guide to Deep Tech 2023 report. From climate change to geopolitical tensions, all problems have turned to deeptech to seek solutions. Investors interested to profit from deeptech need to be aware of these, but also to consider the different scale of funding already available in any given sector and the funding needs of various deeptech solutions before they can hit revenue.

For instance: to develop and commercialise a nuclear fusion reactor for commercial energy generation you are forced to rely entirely on investor funding and peg the story and milestones to drive this on entirely technical achievements. You are also likely in need of a fairly large amount of initial funding just to get the initial prototypes off the ground and ensemble the company team. Conversely, other deeptech startups may be able to close revenue-generating contracts a lot earlier in their lifecycle, such as aerospace technologies that are able to be deployed effectively at smaller scales as they keep on developing larger and more powerful systems.

The interplay between these two factors determine the competition faced by investors as they seek to deploy, the realistic ownership targets they can achieve if they invest, as well as the dependency on equity fundraising to hit strong revenue that can sustain or help sustain the ongoing R&D and business growth.

How is deeptech leading the transformation of industries?

Startups in the deeptech space are often founded and led by researchers or experts within the field. This expertise enables them to identify the root of a problem and devise innovative solutions. For example, in our portfolio, Dr Guido Monterzino and Anmol Manohar (CEng) co-founded Greenjets, building ultraquiet and long range electric propulsion for aerospace; Dr. Pahini Pandya, a life scientist, founded Panakeia.ai, an AI startup focused on cancer diagnostics; Similarly, Scientists Andrea Rocchetto, Giacomo Ciccarelli and Roberto Osellame co-founded Ephos, which is commercialising photonics technologies for quantum computers.

Having founders who are experts and researchers helps these startups stay committed to solving fundamental problems, a focus that is less common in the “generalist tech” startup ecosystem. However, despite being focused on commercialising technical breakthroughs, deeptech does not automatically mean university spinout. In the UK, 17.1% of deeptech startups emerge from educational institutions, which is a substantial number but also means about 8 in 10 are not.

Alright, it’s revolutionary but what about the returns on investment?

Startups in the deeptech sector cannot monetise their products before launching them in the market, and given the complexity of their products, investors need to be patient and invest substantial capital. However, according to a report by BCG, there is almost no difference in the internal rate of return (IRR).

Europe experienced a significant increase in the value of successful deeptech startup exits, jumping from $8.3 billion in 2022 to $59.9 billion in 2023. This dramatic rise underscores a growing investor confidence and market maturity in the deeptech sector.

As shown in the graph, even ignoring the abnormal spike in 2021 and the strange case of ARM, which was taken private post public exit and then re-listed in 2023, IPOs and SPACs continue to remain a robust exit market for public listings and mergers. Moreover, acquisitions and buyouts remain a steady exit strategy, suggesting that larger corporations continue to see value in integrating deeptech innovations, with 2022 and 2023 numbers in line with the 2018-20 period.

This trend expresses increasing importance and potential profitability of deeptech ventures in the European market, which was further highlighted by a recent McKinsey report I obtained by the firm and shared via LinkedIn. By leveraging Dealroom data, they highlighted how Deeptech may have a different risk profile than traditional tech, with a higher element of technical risk and lower market adoption risk, but different does not mean higher, nor facing any higher failure rate than traditional tech companies.

Deeptech companies are also about 10% more likely to scale to unicorn than non-deeptech firms (0.62% chances vs 0.54% chances) and take just as much time to achieve ultimate outcomes, with a median of 6 years to hit unicorn status vs 5.5 for traditional tech and a median of 7 years to exit for both types of firms. This is because, despite a longer R&D phase in the early stages, deeptech firms scale up much faster when they do hit commercialisation. Returns from deeptech may therefore take longer to show the first cash returns, but later catch up to be on similar timelines with traditional software startups.

Data also seems to dismiss another myth surrounding deeptech companies, that of capital efficiency. As a matter of fact, deeptech startups are more capital efficient than regular tech companies, because efficiency does not necessarily equal magnitude. In practice, just because deeptech firms are likely to require more capital to scale over their lifetime, the return on that capital invested for the firm (and the investors backing it) are actually higher.

Specifically for investors underwriting the sector, Preqin data seems to show a higher rate of return for firms deeptech focused VC funds when comparing tech funds since 2003 (16% weighted net IRR vs. 10%). While Europe has not seen many deeptech-focused funds closing and reporting IRR, the expected performance should be in line with global benchmarks historically, driven by similarly attractive regional characteristics for deeptech, and similar net IRR performance for the broader tech funds.

The time is now, and Europe is a prime market

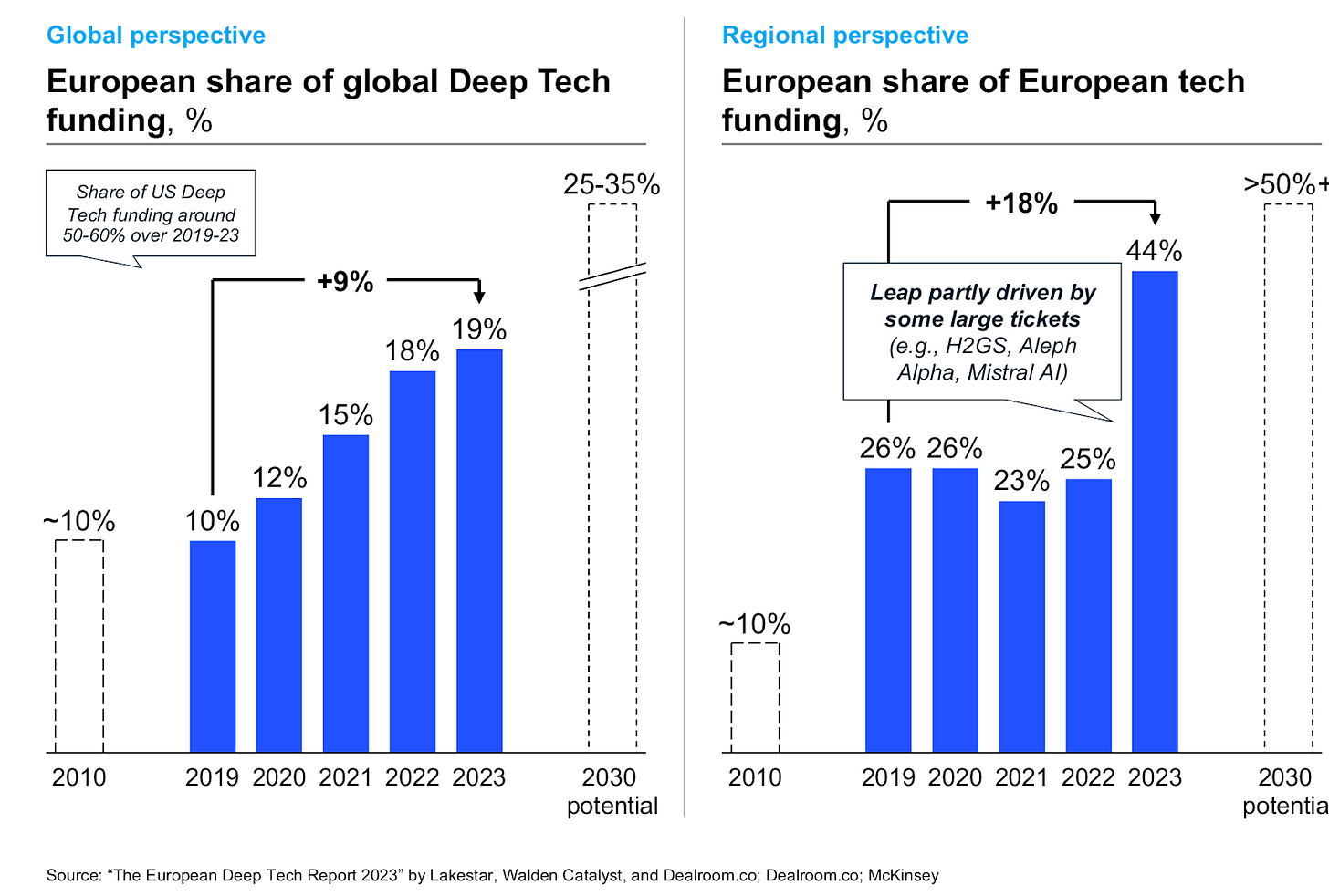

European deeptech is increasingly gaining relevance, both regionally and globally, with a 9% increase in its share of the global deeptech funding and a 18% increase in its share of local overall tech funding.

Yet European investors are falling short in their capacity to back the sector potential all the way to exit, with about 40% of growth capital (Series C+) coming from non-European investors and about 60% of the top acquirers being non-European corporations.

As an early stage investor, this may not matter: ultimately if it’s a US VC that backs late stage deals, or an Asian corporation that buys them, or the Nasdaq where the company decides to IPO, the early stage investor will win. Maybe even more so, since they have the arbitrage advantage of a market where VC competition for deeptech deals is lower when compared to more established markets, such as the US. However, this situation underscores the problems linked to a fragmented Europe where each country myopically focuses on their local market and fails to hit global scale. The fragmented corporate law market, government funding market, IPO market and the lack of large technology-driven corporates and of appetite from local pension funds to invest in the venture capital asset class for now seems to prevent Europe from developing a truly local pan-European growth stage VC and exit market.

Yet I remain cautiously optimistic. Let us not forget that Europe didn’t even have a VC market at all only about 20 or so years ago. With time and a combined effort from all the stakeholders involved, it may be hard but not impossible for Europe to also establish a much stronger later stage capital market. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

For now, the interest from foreign investors and corporations are helping companies grow, validate the local entrepreneurs, and reward early stage VCs and their limited partners. Success tends to breed success.