From Hope to Reality: Former LP Backing European VC Funds On Why Europe's "Permanently Stuck in Second Gear"

The Brutal Truth: Why This American VC Left Europe's Tech Scene and What It Reveals About the Continent's Trillion-Dollar Problem

"Europe is nothing without America," declares American fund manager Désirée Cachette. Five years after moving to Europe with dreams of building a billion-dollar fund-of-funds to catalyse the continent's startup ecosystem, Désirée went back to Silicon Valley and has a stark message for European tech: it's time to face reality.

I sat down for a virtual coffee intrigued by why Désirée was so hawkish on the Old Continent and its tech scene.

The Initial Dream

When Cachette first landed in Europe in 2017, she saw immense potential. Fresh from success in New York's emerging tech scene, where venture funding had grown from $5 billion to over $17 billion annually, she believed Europe was poised for a similar trajectory.

She wrote about her enthusiasm and her LP investment appetite on Medium: “if you are a european founder you no longer should feel the pressure to leave your native country to start something awesome. Likewise, if you are a venture capitalist you hadn’t worry that Europe isn’t “stable enough” in fact I would argue the opposite, as the founding and General Partner of a global fund-of-funds I’m constantly looking for great venture capitalists who share this vision”.

Exit Data From 2016 Désirée Referenced in Her 2017 Blog.

She then set out to launch and, after her fist closing, deploying her ambitious FoF looking for European exposure. She started adding positions up.

The Wake-Up Call

That optimism has since evaporated. Her disillusionment stems from firsthand experience managing cross-border investments and witnessing what she describes as systemic issues in European venture capital.

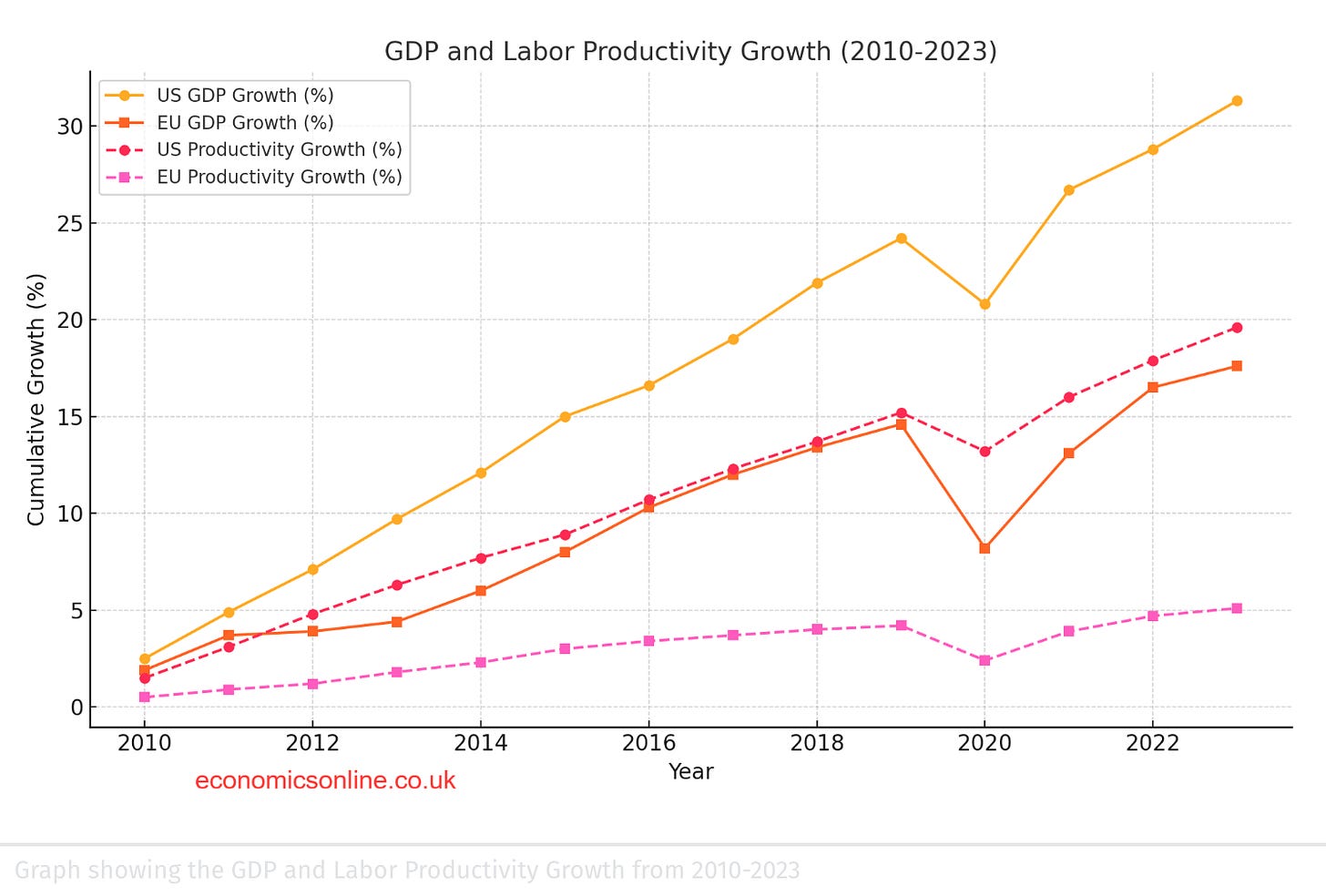

During our call, she doesn’t bite her tongue: “Europe needs to grow up. It's being a big baby”. As a VC investing in deeptech, including defence tech, I must agree that dependence to the US is undeniable. Arguably, Europe’s worries and scrambles to fix its defence woes now that Trump is in office stem from its inability to stand on its own legs without the US or NATO. Economic growth and productivity look equally bleak for Europe compared to the US at present.

The Mathematical Reality In Tech and VC

The numbers tell a sobering story. Cachette calculates that European venture capital has peaked at roughly €50 billion - a ceiling she believes is unlikely to be broken. Even if Europe breaks past that, most of the growth will be fuelled by US money anyway, which is as I wrote before casts doubts on whether Europe can build a strong, independent full-stack ecosystem (from LPs down to founders and from pre-seed to growth and exit) without forcing founders to look for US solutions if they really mean to go global. This assessment comes from analysing both capital availability and deployment capability, with Cachette arguing that even seemingly impressive announcements - like a recent Swiss 50 billion venture fund announcement - are "mathematically impossible" given the region's limitations.

One of the most significant issues Désirée identifies is the mismatch between capital availability and deployment capability. "Even if you add up all of Europe, it's still not as big as the West Coast in terms of market," she tells me.

The Pension Problem

A critical issue Cachette identifies is the absence of European pension funds from venture capital. "The pensions are not outperforming inflation," she notes, creating a vicious cycle where institutional capital remains on the sidelines. This contrasts sharply with the American model, where pension fund participation has been crucial to ecosystem growth. There is no way the cycle of funding can be broken, until the LP ecosystem, including from pension institutions, matures in Europe and backs true large-scale pan European VC as a focus asset class.

Even if some European countries are putting some effort into making pension funds write some cheques into local VCs, the market fragmentation means Europe is still a collection of small ecosystems, rather than building together a stronger market.

“I learned a very hard lesson with Brexit.” Désirée tells me. “We had invested into a fund in the UK… [because] we wanted a high risk early stage fund that was going to give us access to early stage Europe.” But then the market split and their government LPs’ mandate meant the UK, which represents by far the largest VC market in Europe, was not part of Europe anymore. Désirée shakes her head: “my whole strategy, my whole investment memo out the window, just like that.” You can’t be serious about European tech and VC growing if not even Europeans care about Europe.

The Cultural Divide

Perhaps most concerning is what Cachette sees as a deeper cultural issue. "Europeans love to take advantage of Americans," she observes, describing experiences where European partners would deliberately delay capital calls during critical investment periods. This behavior, she argues, reflects a broader reluctance to embrace the speed and decisiveness required in modern venture capital.

European investors, all the way from VCs to their LPs who often mandate bureaucratic behaviours and checks in endless LPAs, are in fact so slow and reluctant to take advantage and support their own ecosystem that Americans are stepping in. The amount of US money flowing in is increasing and that may be good for founders and maybe seed VCs, but not so much for Europe. Pension funds (and their underlying pensioners), Universities via their endowments, family offices and high net worth individuals, as well as any dream of European tech sovereignty, are all increasingly missing out from the party.

As she put it in her 50 Billion Dollar Elephant Piece, Désirée is convinced she launched her fund of funds backwards: “I should have raised the funds in the US and deployed in Europe ─versus raising in Europe to deploy Globally”.

Europe as Training Ground

Rather than competing directly with Silicon Valley, Cachette suggests Europe should embrace its role as a "training ground" - a place where founders and fund managers can learn and make mistakes before entering the "big leagues" This perspective might be uncomfortable for European tech leaders, but Cachette argues it's better than maintaining unrealistic ambitions.

We both discuss how Israel made a success out of this, and that the only alternative would be to build a strong pan-European market. Désirée is sceptical that the latter is a real possibility.

“Look at Spotify. Anytime a European startup actually gets successful. What happens? It comes to the US. It becomes a US company. I think the top talent will always come to the US.”

The Broader Implications

The consequences of Europe's venture capital limitations extend beyond startups. Cachette points to broader economic and social challenges, including:

- Pension fund underperformance threatening social safety nets

- Brain drain as successful startups inevitably relocate to the US

- Growing dependency on American capital while maintaining an antagonistic stance

- Limited innovation in fund management due to comfortable but unambitious practices

On the bright side, although more limited in ambition, is the possibility to gain from the arbitrage when scouting promising startups who will eventually grow in the US. It's nice to try and help Europe. But we also need to be realistic that, as long as there isn’t a true pan-European scale-up market, founders are better off thinking of a US strategy already after their pre-seed or seed.

Looking Forward

For European founders and investors, Désirée’s message might be hard to swallow but offers a practical framework: use Europe for product-market fit and early validation, then look to America for true scale.

This approach, while perhaps not what European tech leaders want to hear, might be the most realistic path forward for founders and a warning signal for stakeholders to finally do something that’s not just endless regulations and country-specific actions.

The irony, we note just before finishing our call, is that Europe's perceived weaknesses could be strengths if properly embraced. The smaller scale allows for less expensive mistakes, while stricter regulations in areas like food tech can provide valuable validation for global expansion. The question is whether Europe will ever want to play the major league in tech sovereignty or remain a fragmented collection of trampolines for founders and small VCs to shoot for growth in the US.