Why new VC funds offer the greatest opportunities in Venture Capital

Emerging VC funds offer high return opportunities, a new research shows. But interested investors also have to take into account major risks.

“Among the 10 best VC funds of a given year, a disproportionate number of investment firms are represented with their first or second fund”

Mark Schmitz, Equation Capital

New venture capital firms are often particularly successful in startup investments. This is the result of the analysis carried out by the Munich-based investment platform Equation, which provides capital to venture funds: what the industry calls a Limited Partner or LP. “Among the ten best start-up funds of a year, a disproportionate number of investment firms are represented with their first or second fund,” says Equation founder Mark Schmitz.

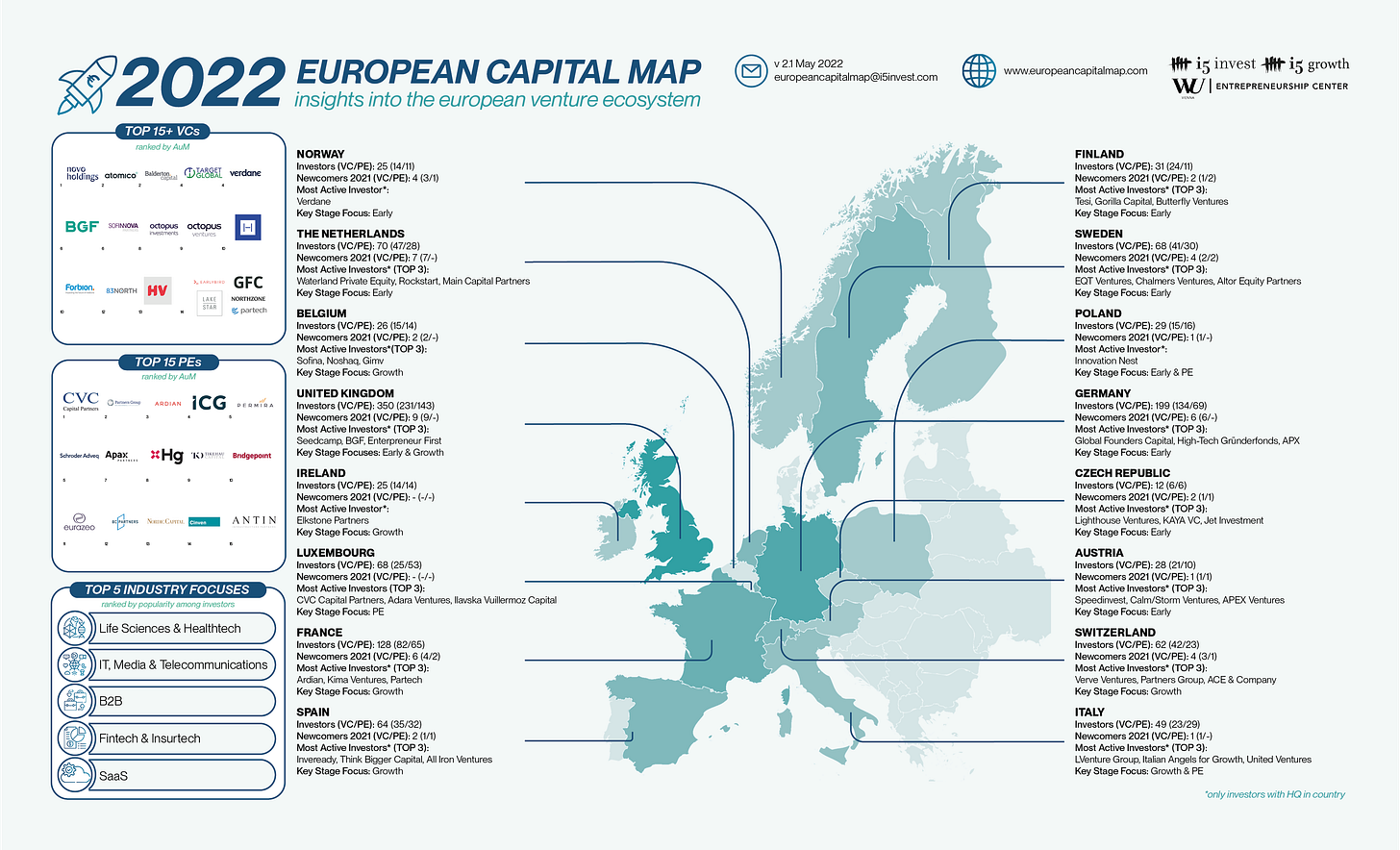

Competition among venture capital firms in Europe has increased enormously. There are now 550 active European venture capital firms according to the European Capital Report 2022 by the consultancy firm i5invest.

48 new venture capital firms were launched in 2021 alone and, statistically speaking, the probability of top returns is particularly high amongst these. "The results contradict the common perception," says Schmitz, “Because investors are historically more likely to rely on established firms”.

Venture capital firms raise money from high-net-worth individuals, family offices, pension funds and other institutional investors and, with this capital, they invest in startups. If their portfolio companies are later sold or go public, or if late-stage investors buy shares at a premium via secondary market transactions, the money flows back. Sometimes the returns can be spectacularly high, with the best funds in the world, which were launched about ten years ago, now repaying their investors 25 times their money and more. These prime yields are the focus of Equation’s research.

Because there are good and bad startup years, VC funds are always compared on the basis of their launch time. As with wine, the venture capital industry speaks of “vintages”.

Equation has evaluated figures from the Cambridge Associates database for the US market: Between 2004 and 2016, significantly more new venture capital firms made it into the ten highest-yield funds of their year. In eleven out of 13 vintages, more newcomers with their first or second fund came into the top ten than established competitors. Twice they were tied ─although there were always significantly more established investment firms contending the crown for any given vintage.

New venture capital firms are more successful: According to data by Cambridge Associates (2019), VCs in their first or second fund are disproportionately more likely to make it into the top 10 performers

Schmitz’s co-founder at Equation, Reiner Braun, has been researching venture capital for years as a professor of corporate finance at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). Based on the research, the two assume that the pattern is transferable to Europe.

An example of a German premiere hit is Point Nine. The first fund of the company, which was launched in 2011, has resulted in the Dax group Delivery Hero, among others, and the banking software provider Mambu, which is currently valued at €4.9 billion. In the UK, the first proto-fund for pre-seed investor Entrepreneur First recently announced cash-on-cash return to its LPs worth 17x the capital invested.

https://twitter.com/matthewclifford/status/1512375418799763461

In Europe too, therefore, investors in first-time funds have a higher chance of exceptional returns. But why is that?

The Equation team suggests three reasons for this.

1. Young funds invest particularly early

First of all, the funds differ in size. A first-time fund holds an average of $46 million, the fourth edition a good $190 million, and for the seventh funds it is an average of $300 million. The fund size correlates in which startup phase investments are made. Small funds tend to invest in startups early, large funds in the growth phase when the need for capital increases.

One thing applies in principle: the earlier an investor gets involved, the greater the risk and return opportunities. But TUM Professor Braun says that the higher probability of achieving particularly high returns “cannot be explained solely by structural differences such as the investment phases.” However, recent data from Dealroom, suggests the most successful “unicorn hunters” (VCs capturing billion dollar startups) are the ones backing these companies at seed.

https://twitter.com/francesco_srv/status/1531976541193871362

Furthermore, a small fund is “easier to multiply”.

Let’s say a $10m VC invests an average of $500k in early seed rounds of $2m at an average of $8m pre-money valuation: this investor now should own about 5% of their investee companies ($500k is 5% of $10m). Let’s assume this investor spends 15% of the fund in fees and does not have any mechanism to recycle these and that all the fund is invested in first cheques with no follow-on capital reserved for later rounds. This VC would now have invested $8.5m across 17 companies.

Let’s say now that one of the these investments becomes a unicorn after 5 investment rounds and exits at that valuation. Let’s model 20% dilution at each round. The VC would own 1.64% of the company at exit: 5

That’s $16.4m back to the VC out of a single company! The fund is already over 60% up from its initial capital because of a single unicorn. With 16 more companies to go, this fund could very well be on the path to the top-quartile returns VC funds aspire to.

Conversely, a $150m fund backing the same 17 companies would have barely spent ~5.6% of its capital and, despite capturing a unicorn, it would have recovered just over 10% of its fund from this “success”. It would therefore probably avoid doing $500k cheques and look for bigger rounds, where it could deploy a few millions per ticket, which means coming in later and enjoying less of the upside. It would then need to reinvest more money into the best performing companies of its portfolio, needing bigger and bigger exits to justify the the cost of its deployed capital. Suddenly this type of funds needs decacorns (startup worth $10 billion or more) rather than unicorns ─and ideally several of them. This makes it practically impossible for large funds to achieve the 17x level of returns generated by Entrepreneur First with its first cohort.

On top of this, as Schmitz’s partner Andrea Casasco points out, investors in the very early rounds tend to be more insulated by the hyper-inflation that affected the growth stage valuations in recent times, and that is likely to cause the biggest losses in case of a market downturn.

https://twitter.com/CasascoA/status/1486655247586050050?s=20&t=5Vnw0VrNIH0J8rr5ggWU1A

2. Emerging venture capital firms focus on trends at an early stage

New venture capital firms are also betting on new trends, according to another part of their analysis in which Equation compared venture capital funds in Europe founded since 2016 with older ones. For example, the younger funds have made 6.1% of their investments in decentralised ledger technologies such as the blockchain, the older ones only 1.6%. “We even see funds that specialise in the areas of climate technology or aerospace, for example,” says Schmitz.

New funds raised for any given vintage: Chart from Equation on Handelsblatt using Crunchbase data

The investor’s explanation: “If there are new trends and sectors to open up, then those who are already active in the industry must first rethink.” New firms can put together teams that are familiar with these trends from the outset and may have even been driven to venture capital in the first place to capture a trend early where they have unique expertise.

3. New fund managers have different work experience

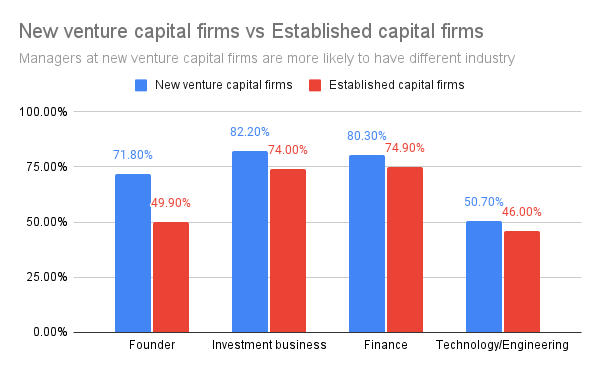

TUM and Equation have also found differences among decision-makers, especially in terms of work experience. 72% of fund managers at emerging venture capital firms have previously founded their own companies or worked for startups in various departments, from finance to technology, and can pass on this experience. For the established, this only applies to half.

Data Equation 2022 based on Crunchbase*

Nevertheless, investors should be cautious when investing in new funds: there is also an increased risk of default. The stronger the competition, the harder it is for new investment firms to win the best deals. For startup founders choosing a VC partner to receive funding from, especially the best ones who often have multiple options, a good network and references are often crucial when making the choice. Whether a new team is plugged into the ecosystem and has a good reputation in the market is therefore a key aspect to diligence for someone looking to back emerging VC managers, Schmitz argues.

Emerging managers: an opportunity for the European venture capital scene

Across Europe, there is a clear institutional push to encourage new VC funds to join the market. In the original German article where Equation decided to publish their research findings above, it was reported that the German government deliberately wants to help the birth of new venture capital firms, which often lack the trust of private investors. Germany has even its own government-backed LP investor to invest in funds who are heavily focused on investing in Germany: KfW Capital. This is the same across Europe: where each large nation has a similar institutional LP fund, such as Italy’s CdP Ventures or the UK’s British Business Bank. There is then a EU-wide initiative too, the European Investment Fund, which really kickstarted the whole government-backed fund of funds brigade and often pairs up with national funds in backing new VCs ─other than with the UK one of course, because… Brexit.

Government-led initiative want to make targeted investments in areas “where the European market still needs to be pushed,” says Anna Christmann, startup representative at the German Federal Ministry of Economics. “Especially if the risk for the market is too great, we can use public money to provide incentives,” she notes. Investments by KfW Capital are therefore often used to support first-time funds. According to Christmann, this was most recently the case for 20 percent of all fund investments. Other national funds have similar agendas, with the British Business Bank for example running a specific programme for first-time funds called the Enterprise Capital Fund.

Yet, programmes of this nature often come with strings attached and, on top of being quite bureaucratic to navigate and manage, they normally tend to back only people with established traditional track record in venture capital and with a very specific geographic focus. Therefore, whilst 10 years ago it was almost unthinkable to start a fund in Europe without government support, today more and more emerging VCs chose a different route to market, which often comes with more freedom to operate across geographies and with more diverse team backgrounds.

Not for laymen: Great opportunities, high risk

According to Greenspring Associates, an LP with $11 billion assets under management, of the 180 VC funds analysed under its portfolio management program, emerging fund managers edged out more established GPs (Net Multiple +0.10x; Net IRR +0.87%). A Cambridge Associates report agrees: “Today’s market is not the same as 20 years ago. Broad-based value creation across sectors, geographies, and funds means success is no longer limited to a handful of (often inaccessible) fund managers. Moreover, top returns are not confined to a few dozen companies. New and developing fund managers consistently rank as some of the best performers.“

As we have seen, there are 3 reasons why emerging fund managers might have slightly better performance than established VCs in today’s environment:

First, most emerging firms raise small funds. Smaller funds generally outperform, as they can participate meaningfully in early rounds and a single outlier has the potential to generate strong fund-level performance, even if the fund is only able to garner modest ownership.

Second, emerging fund managers tend to be made up of a smaller group of GPs or solo capitalists with strong industry insights and personal brand in a specific industry or trend, often when this is still nascent and overlooked by the established players.

Third, most emerging fund managers do not have to worry about succession plans or manage an existing brand and track record. They can be focused on deliverying on their chosen strategy,

Finally, data shows that the venture capital industry has strong reversion-to-the-mean effects, which implies that the Midas Touch tends to rub off over time—after about 60 portfolio company investments (See The Persistent Effect of Initial Success: Evidence from Venture Capital, § 3.2): “Little, if any, persistence [occurs] beyond the 60th portfolio company, implying long-term convergence to a common mean”.

The bottom line is that emerging fund managers have indeed an edge compared to established VCs in terms of fund performance. On the other hand, as with most investment opportunities, greater upside also means a greater risk. Therefore any investor looking to back successful new firms ultimately needs to be able to assess whether the managers of such VC funds have the ecosystem connections and unique insights to deliver on their investment thesis.

Credit/Thanks: A big part of content for this English article was based on a German interview by Luisa Bomke and Larissa Holzki from Handelsblatt with Equation Capital’s founder Mark Schmitz and data from his firm’s research